The Path to Jetex

– the Wilmot Mansour Story by John Miller Crawford

Three model aeroplane hobbyists build a business - 1910s-1938

The Wilmots’ first production - The Aeroplane World, Dec. 17, 1918 Jetex has its origins with three remarkably enterprising and talented young men, in England in the early part of the twentieth century.

Two of the three were the Wilmot brothers, Charles Mandeville ('Bill') Wilmot and John Wilmot. As schoolboys in the second decade of the century, fired with enthusiasm for the exciting developments in aviation, they produced and sold their own hand-written magazines, The Aeroplane World (above right) and The Aeroplane Monthly.

The third young man, initially working quite separately from the Wilmots, was Joseph Naimé Mansour, a talented model-maker whose craftsmanship had achieved early recognition. He had accepted an invitation to contribute to the most prestigious example of the modelmaker's skill ever created in Britain – the 1:12 scale Queen Mary's Doll's House (right), still today a major attraction at Windsor Castle.

With the burgeoning interest in aviation that had already attracted the Wilmots, Joe Mansour turned to modelling aeroplanes. Not content with the relatively heavy stick-and-silk models then dominating the scene (balsa wood was not yet available), he developed a method of lightweight construction using moulded papier-mâché. This he produced by compressing a mixture of newspaper and glue through the family laundry mangle. He then moulded the resulting sheets into very light but strong fuselages. (It's interesting to consider that the Jetex 'Tailored' series of the 1950s also used moulded fuselages.)

With his moulded fuselage process perfected, Joe Mansour's enterprising spirit turned to a scheme for commercial production. So, in 1931 he advertised in Flight magazine for others to join him in setting up a business to develop and manufacture model aeroplanes. The Wilmot brothers, who meanwhile had been experimenting with fuselage construction from very thin aluminium sheet, responded to Mansour's advertisement.

In what was to prove a typical businesslike move, the trio formed two companies in 1931. One, Wilmot, Mansour & Co., Ltd., held patents which they had been granted, and the other, International Model Aircraft Ltd. (IMA) had the world's largest toy manufacturer, Lines Brothers, as a shareholder (right). IMA was responsible for production, which was eventually conducted in the large Tri-ang factory in Merton. The Tri-ang football field adjoining the IMA factory was to became a model aerodrome, where customers could learn to fly the models coming off the production line.

IMA's initial product was to be an innovative model aeroplane with an aluminium fuselage and paper wings – the FROG Interceptor fighter Mark IV (below right). Not only was the Interceptor unique in its method of construction, but its motive power also showed innovative flair. It was powered by a rubber motor which turned the propeller via a minute Swiss-made gearbox, allowing a smaller, more realistic, propeller to be used. The rubber motor could even be wound up by means of a high-speed geared winder built into the model's box.

Moreover, in an era when the rudimentary appearance of model aeroplanes bore little similarity to contemporary full-size aircraft, the Interceptor stood out with its semi-scale resemblance to the Supermarine Schneider racers. With a propellor speed of 2,700 r.p.m., it was quite the fastest rubber-powered aeroplane to be bought – typically, it travelled 300 feet at a height of 70 feet and a scale speed of 240 mph.

The 'FROG' name came from Joe Mansour, who had coined the acronym from the slogan "First to Rise Off Ground", to express the advantage his papier-mâché models had over the stick-and-silk machines. Later, it came to signify "Flies Right Off Ground". A 'W'and an 'M' were incorporated in the FROG logo (below right). By November 1932, the Wilmots and Mansour had achieved their goal of commercial production with over 800 Interceptors per day being produced.

Taking advantage of Tri-ang's world-wide outlets, the Interceptor was by 1933 being produced in the colours of many different countries, and being built at the rate of 1000 per day. The initial price of 10/6 was reduced to 7/6, and eventually to 5/-. Sales kept climbing, and the original Interceptor model remained in continuous production through till 1940.

Faced with the problem of frequent breakages of the Interceptor's carved wooden propeller, the IMA designers once more showed their inventive flair by moulding the propellers from cellulose acetate. The material proved such a success that most small parts for the FROG flying models were subsequently made from it. Later, it was to have an even bigger role as the material for the FROG Penguin non-flying scale models.

In 1934, IMA's next model was introduced. This was a scale D.H. 80A Puss Moth, made famous by the long distance flights of Amy Johnson, Bert Hinkler, and Jim Mollison. Emboldened by success, in 1935 the company released its most ambitious flying scale model, the Hawker Hart, with three rubber motors geared together, and rigging sprung to minimise damage. However, the production difficulties of this complex model proved costly for IMA.

IMA letterhead

Learning their lesson and taking advantage of the advent of balsa wood, the Wilmots and Mansour in 1936 introduced other simpler and lighter models. In a further ground-breaking move, they produced kitsets from which enthusiasts could build their own model aircraft. These first FROG kits were of very high quality, comprising die-cut parts, printed tissue, dope, and brushes.

Not neglecting the ready-to-fly market, IMA also introduced a development of Mansour's original model aeroplane, having a moulded-paper fuselage with balsa wings. Lighter and easier to manufacture than the Interceptor, this was turned out in very large numbers and a variety of types and sold in Woolworth's department stores. More expensive and larger kits, a Spitfire, a Vickers Wellesley bomber and a PV.6 dive bomber, were sold at specialist toy shops. By the end of 1936, IMA had 21 models on the market.

1937 saw yet another innovation with the introduction of the first three moulded non-flying scale models, known as 'Penguins'. These were moulded in cellulose acetate and were very detailed, giving the modeller practically everything needed to build an accurate scale model. (Read more about those models and ther history of FROG on the profusely illustrated FrogPenguin.com website.)

The Jetex motor is conceived and created – 1938-1948

Never ones to rest on their laurels, the Wilmots and Joe Mansour conceived the notion of adding rocket boosters to their flying models. The challenge was to concoct a propellant that would provide a safe and even thrust over several seconds without risk of setting the model aflame. One of the IMA directors, Capt. E Grattan Thomson, put them in touch with Group Capt. C H Keith, an armament specialist who could give them access to the necessary technical knowledge and expertise.

Many experiments ensued and by the end of 1940 they had a prototype motor, composed of a Bakelite case enclosing a removable cardboard tube holding a gas-generating compound which could be ignited with a fuse. Fitted to model aircraft of various sizes, the motor proved so successful that the British War Ministry, by then in the midst of the Second World War, saw the possibilities of adding another type of device to their arsenal.

The Development of Miscellaneous Weapons Department (DMWD), led by Commander Neville Shute Norway, the famous aeronautical designer and author, took charge of the project and a senior Government pyrotechnical chemist was assigned to join the team. Another team member, from the IMA factory, was A A (Bert) Judge (right), winner of the 1936 Wakefield contest and later to become the Jetex Chief Designer.

The DMWD also brought Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) into the act, as manufacturers of wrapped cordite charges for engine starter cartridges and thus having suitable facilities for large-scale production of the Wilmot-Mansour rocket motors. Research on a suitable fuel was conducted at ICI's Nobel Division in Ardeer, Scotland. This research was in the hands of a young (30 year old) chemist, Alex Hutchison (below right). His great contribution to the success of Jetex was to invent the fuel itself, the low-temperature, steady-burning fuel that was so different from the earlier nitrocellulose propellants. Hutchison's unique formulation was patented under his name in 1948.

Meanwhile, the IMA factory under Joe Mansour continued with model aircraft production, principally turning out millions of recognition models for the Forces, but also keeping on producing the ready-to-fly Spitfire model.

Bill Wilmot became involved in another Government war project for the Airborne Forces Experimental Establishment (AFEE), involving the design and trialling of 16 ft and 32 ft towed target gliders. The development work was initially conducted at the Thame RAF airfield, with production craft being manufactured at the Lines Brothers factory at Merton.

On a parallel track, Joe Mansour was charged with the construction design of a target drone, with four feet wingspan, to be used by Wrens (Women's Royal Navy Service) to teach merchant seamen to 'lay off' when attempting to shoot down enemy aircraft. In due course, because the seamen became very proficient in shooting down this slow-flying aircraft, Joe Mansour's IMA team was asked to develop a faster-flying rocket-powered model. This was of pod-and-boom configuration, with a fuselage of moulded papier-mâché (shades of Joe's first models!) in four sections glued together over a balsa keel and formers with wing and tail of balsa and fabric construction, the whole sprayed bright orange (right).

The rocket propellant was cordite-based (nitrocellulose smokeless powder); the guanidine nitrate based Jetex micro rocket fuel was still to come. The motor weighed two pounds (0.9 kg), with a maximum thrust of just under three pounds (1.4 kg). So successful was it for its purpose that IMA turned out hundreds of thousands.

With their wartime activities entailing a reduced involvement in the management of IMA, Bill Wilmot and Joe Mansour chose to sever their relationship with that company in 1944. (The original trio had been reduced to a duo with the death of John Wilmot in a car accident in 1943.) Their commercial ambitions were now focused on powering model aircraft with smaller rocket motors of the gas-generating type used in their target aircraft. Manufacturing premises were obtained in Bishop's Waltham in Hampshire and five staff were employed. As a name for this enterprise they turned to a company which they had incorporated in 1932 – Wilmot, Mansour & Co., Ltd.

War work also continued, with the two development tracks of Wilmot's towed target gliders and Mansour's powered target drones merging in rural Hampshire as a combined project. Initially, the work was carried on at Marwell Hall, where the estate has been requistioned for a wartime aerodrome, and then at the AFEE site at Beaulieu Aerodrome. Target gliders and rocket-powered craft of various sizes, ranging between 4 ft and 32 ft were designed and tested. At Beaulieu, Wilmot and Mansour had the use of a small hangar in which a Spitfire XVIII was converted into a target tug. The hangar also housed model aircraft which were used to test the model motors developed at the Wilmot Mansour factory in Bishop's Waltham. Research and development on suitable fuel for the motors were conducted at the ICI factory in Scotland.

The two young sons of the CO of the RAF Beaulieu experimental station between 1945 and 1947, Chris and Robin Heath (right), were pressed into service as juvenile 'test pilots' of simple gliders powered by the model motors. As Chris recalls, "they worked very well and on occasions, we had to spend a good deal of time and effort chasing these planes across the heath", with the result that "apparently Wilmot and Mansour decided that if their invention survived the Heath children's handling and mishandling, the Jetex toy was a good idea".

In 1947, by when all motor development and production had been consolidated in the Beaulieu hangar, it was purchased from the government and moved to Totton, a nearby suburb of Southampton, to become the permanent headquarters and factory for Wilmot, Mansour & Co., Ltd (above right). By this stage, the composition of the gas-generating propellant for the model motors had been fixed, and patented, as principally consisting of a guanidine nitrate oxidiser base with nitrated resorcinols as a catalyst.

ICI was contracted to manufacture the propellant in quantity. E F H Cosh, visiting the ICI plant in Scotland with other journalists early in 1948, was shown motors of two types. One was a self-contained cartridge (right) of the type depicted in the March 1948 patent. The other type, "for the more advanced modeller", comprised "aluminium alloy jet motors, fitted with a special safety device [and] loaded with a pellet of gas-producing composition". He was able to witness "the 'Jetex' units flying tailless models in gusty weather conditions, and was particularly impressed by their stable performance". He reported that the motors would be "marketed towards the end of May".

The Wilmots’ first production

- The Aeroplane World, Dec. 17, 1918

Souvenir Book of Queen Mary's Doll's House, on which Joe Mansour worked

- Olney & Son, 1924

An IMA letterhead, showing Wilmot and Mansour as directors along with the Lines brothers

- FROG Model Aircraft, 1989 (p. 10)

FROG Interceptor and box

- Aumann Auctions, 2005

FROG logo ('W' and 'M' hightlighted)

- Meccano Magazine, Dec. 1948

Advertisement for FROG kitsets

- Popular Flying, Feb. 1937

'Bill' Wilmot (left) and Joe Mansour

- FROG Model Aircraft, 1989 (p. 10)

IMA announces the acquisition of "designer-pilot" Bert Judge in 1937

- reproduced in FROG Model Aircraft, 1989

Alex Hutchison at the time of his

work on Jetex fuel

- Alex Hutchison

IMA target rocket plane,Tangmere Aviation Museum

- Howard Metcalfe

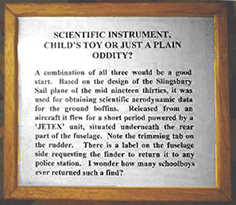

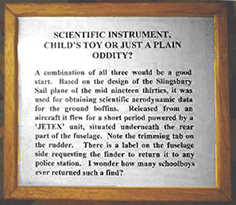

Label for the IMA target plane, Tangmere Aviation Museum – somewhat misleading, but it does mention "Jetex"

- Howard Metcalfe

Former Jetex factory (previously Beaulieu

hangar), Totton, in 2001

- David Carpenter

Robin (l.) and Chris Heath, Beaulieu 194

- Chris Heath

- UK Patent 645,897, 3 Mar. 1948

Acknowledgements

Text by John Miller Crawford, based on the following sources provided by David Carpenter, Bill Henderson, Edward Jones and Stuart Guy:

- Editorial obituary: Joe Mansour, Aeromodeller, January 1973

- Coles, R. History Of Beaulieu Airfield, Robert Coles 1982

- Lines, R. & Hellstrom, L. FROG Model Aircraft 1932-1976, New Cavendish Books, 1989

- John May, 'Trixie, Jumbo and Co', Aeroplane Monthly, May 1978 p. 261

- Hampshire - the county magazine, December 1990

- Personal correspondence of Bert Judge to Edward Jones

- Personal correspondence of A W Thatcher (Wilmot Mansour staff, 1961- ) to Stuart Guy (Head of Engineering, GEL Engineering Ltd)

Illustrations:

- David Carpenter, John Miller Crawford, Chris Heath, Alex Hutchison, Mike Ingram, Edward Jones, Howard Metcalfe, Aumann Auctions

The Jetex Heyday

The Jetex Heyday – 1948 - 1956 by John Miller Crawford

Jetex takes off

The first Jetex motors went on sale in June 1948. Using marketing skills honed by years of experience with the FROG brand, ‘Bill’ Wilmot and Joe Mansour executed a cunningly-planned publicity campaign which would ensure that the new micro rocket motors created a sensation in the modelling world. The aeromodelling public had been softened up a month before when the premier aeromodelling magazine Aeromodeller had tantalised its readers by hailing “the latest developments of a new fuel and motor giving an effect of jet propulsion”. Next month’s issue would be “something of a special ‘jet’ number for which an appropriate cover design has been executed by Mr. C. Rupert Moore” (the renowned aeronautical artist). True to its editor’s word, the June 1948 cover depicted a twin Jetex powered Gloster Meteor model in near-vertical ascent (somewhat fancifully, in view of its all-up weight, with fuselage and nacelles carved from solid balsa). Inside the magazine were plans and construction notes not only for the scale Meteor but also for a Zephyr duration model. The editor hailed the “new development in the powering of model aircraft”, and an article was devoted to “Pellet Power Possibilities”. All this editorial content was complemented by the first full-page advertisement (below right) from Wilmot, Mansour & Co., Ltd, announcing two Jetex outfits. These were the Jetex 100 for 27s. 6d. and the Jetex 200 for 37s. 6d. – not exactly cheap, given that on another page Gamages were advertising the FROG 100 1 cc diesel engine for 60s.

Further, in the same issue, the leading Mayfair department store Selfridges advertised "Demonstrations Daily" of "Aircraft, Racing Cars, Speedboats in action", boasting they they had secured "the whole of the initial production" of the revolutionary new engines.

Further, in the same issue, the leading Mayfair department store Selfridges advertised "Demonstrations Daily" of "Aircraft, Racing Cars, Speedboats in action", boasting they they had secured "the whole of the initial production" of the revolutionary new engines.

There was one element strangely absent from the initial Wilmot Mansour product line – models for the motors to power. This absence was especially curious in light of the partners' model-making background, and even more so given their employment of leading designer Bert Judge, later to be be the creator of so many innovative and successful Jetex models. Selfridges, too, must have disappointed many customers who learned that they could not buy the models the store was demonstrating so enthusiastically.

It was left to enterprising commercial kit manufacturers to meet the market demand for Jetex model kits. Veron was quickest off the mark. Its Chief Designer, the talented Phil Smith, produced the Air-O-Jet (right) and it was on the market by November of 1948. Keilkraft was not far behind. From the drawing board of the versatile and prolific Bill Dean came two versions of his Skyjet, one for each motor, in November. These three kits were a boon to aeromodellers anxious to try out the new motive power but without design skills of their own.

In late 1948, the larger 350 motor arrived, in time for the Christmas market – "Treat yourself this Xmas", said the advertisements). The outfit was priced at 50 s. At 80% of the price of a Frog 100 diesel, this was a substantial slice of youngsters' pocket-money. Wilmot Mansour were clearly conscious of this and enjoined prospective purchasers to remember that they "will not suffer the usual worrying speculations as to whether you'll break the prop. (another 4/6!)".

Even now, there were no models produced by Wilmot Mansour for any of the three motors. The best they could offer in their advertising was the advice (in small print!) that plans for Bill Dean's Jetwing for the 100 unit were "featured in the latest issue of Model Aviation Series".

By early 1949, Wilmot Mansour had become aware that sales of their new model power units were restricted by two factors – pricing and a product range that did not include model kits. They moved rapidly to address both issues.

In May, prices were reduced by over a third on all three existing motors ("now that development and tooling costs have been paid off") and the smaller Jetex 50 outfit (above right) was introduced at just under the critical price point of 10s. It came attractively packaged in a yellow box, which would come to be regarded as classically Jetex (and so provides the background colour for the Jetex.org masthead!). The Jetex 50 proved overwhelmingly popular and, more than any other Wilmot Mansour product, was responsible for the company's commercial success in the years to come.

At the same time, the first models from Wilmot Mansour appeared. This was almost a year after the first motors had been released and even now, they were quite elementary. There was a 40 m.p.h Racecar and the beginnner's Mijet all-balsa 50-powered glider (above right).

By 1951, the Jetex range of kits comprised 10 models, of an impressive variety. There were two high performance duration models, both of them designed by a new recruit to the design team from IMA, the gifted young designer Ian Dowsett. There were scale models, a Meteor for twin 50s and two sizes of Vampire, for the 50 and for the 100. Aircraft models also included a flying wing and two helicopters, for twin 50s and twin 100s, while non-flying modellers were offered two race cars and a hydroplane.

After their dilatory beginning as Jetex kit manufacturers, Wilmot Mansour gave their model design team their head, resulting in some impressively inventive kits. The Zyra Space Ship (1951), the twin-engined SARO A/1 (1952) and, paragons of Jetex kits, the 'Tailored' range of scale models (1952 on) all played their part in establishing Wilmot Mansour in a leading position in the production of model motors and model kits.

If Wilmot Mansour had missed a marketing opportunity with their tardy introduction of model kits, they did have the acumen to take an early initiative that proved to be an inspired promotional success. At the same time that they advertised their first simple models, they also announced the inaugural Jetex Contest and the approval by the S.M.A.E. (for insurance purposes) of Jetex power.

The first International Jetex contest was held at Fairlop Aerodrome in September 1949. In an indication of the interest aroused by the new form of model motive power, there were several hundred entrants, including representatives from the US and the Argentine. From these, 30 finalists were selected. The manufacturers of Jetex fuel, Imperial Chemical Industries, donated a substantial silver bowl to be grandly designated the 'Jetex ICI Challenge Trophy'. The contest was convincingly won by Dick Twomey, the "child aeromodelling prodigy" (as Aeromodeller called him), flying his 200-powered Firecrest.

Prior to this prestigious event, Jetex had gained early recognition at other contests. A year earlier, at the Third International Week at Eaton Bray in September 1948, "in the unorthodox section Minney had been a lucky winner [according to Aeromodeller] with his Jetex powered model which 'flew over'".

In 1951, the S.M.A.E. gave further recognition to the status of Jetex power by establishing a second annual contest for a handsome silver trophy, known as the Jetex Challenge Cup. This was won by Bill Henderson in a field of 53 competitors, flying his legendary Vindskreenviper. This 350-powered craft was a descendant of Puff-Adder, with which he had gained a third placing in the inaugural ICI contest.

These contests continued in subsequent years, though with declining numbers; in 1956, Ian Dowsett won the Jetex Challenge Cup in a field of 18 entries. At the same time, Jetex power had become such an accepted part of the serious aeromodelling scene that it had acquired a class of its own at general model aircraft contests; in that same year of 1956, Jetex events were held at the Stockport Express Rally and at the All-Britain Rally.

Wilmot Mansour did not confine their ambitions for Jetex to the British market. From early on, they believed that there would be a large export market, and they were proved right. By 1951, 60% of Wilmot Mansour's earnings were coming from the export sector. American retail sales alone brought in some £150,000 in that year. Total kit production was averaging some 3,000 per week.

Jetex motors met ready and rapid acceptance abroad, not just in Commonwealth countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada, but also, particularly, in France and the United States. Designers in these last two countries welcomed the challenge of creating model aircraft for the new form of propulsion.

Over the Channel, in France, the leading aeromodelling periodical Le Modèle Réduit d'Avion championed the Jetex cause, publishing plans by leading French designers. Among them, bringing a distinctively Gallic idiosyncracy to their designs, were P. Maillard with Pfupf in 1951, Jean-Claude Aggéry with Puk in 1953, and R. Parlatoré with his "slightly supersonic" Mosca, also in 1953.

On the other side of the Atlantic, in the United States, designers were even more rapidly off the mark with Jetex models. Bill Winter's Swish, for the Jetex 100, was published as a plan by Model Airplane News as early as November 1948, a mere five months after the first Jetex motors had been released onto the British market, and before any had been marketed in the US. In January 1949, Modelcraft Hobbies of New York prominently advertised Jetex model jet motors, "the latest and simplest form of power in the world for planes, cars and boats" (but surely only for models of those). $4.95 was the price and only the 100 outfit seemed to be available.

Just three months later, in April 1949, Model Airplane News, Flying Models and Air Trails Pictorial were all carrying an advertisement by Berkeley for the Sin-Jet (bearing a brasher name than the British kitted models), "the first American made Jetex powered model kit" (right). Jasco was also offering its more mundanely named Jasco Jet for the 100 motor.

By March 1950, American Telasco had become the official US distributor for Jetex and were offering the Jetex 50 for $1.95. In following years, Telasco, Berkeley and Comet all added to the range of kits available to the American modeller.

The Wilmots’ first production

- The Aeroplane World, Dec. 17, 1918

Souvenir Book of Queen Mary's Doll's House, on which Joe Mansour worked

- Olney & Son, 1924

An IMA letterhead, showing Wilmot and Mansour as directors along with the Lines brothers

- FROG Model Aircraft, 1989 (p. 10)

FROG Interceptor and box

- Aumann Auctions, 2005

FROG logo ('W' and 'M' hightlighted)

- Meccano Magazine, Dec. 1948

Advertisement for FROG kitsets

- Popular Flying, Feb. 1937

'Bill' Wilmot (left) and Joe Mansour

- FROG Model Aircraft, 1989 (p. 10)

IMA announces the acquisition of "designer-pilot" Bert Judge in 1937

- reproduced in FROG Model Aircraft, 1989

Alex Hutchison at the time of his

work on Jetex fuel

- Alex Hutchison

IMA target rocket plane,Tangmere Aviation Museum

- Howard Metcalfe

Label for the IMA target plane, Tangmere Aviation Museum – somewhat misleading, but it does mention "Jetex"

- Howard Metcalfe

Former Jetex factory (previously Beaulieu

hangar), Totton, in 2001

- David Carpenter

Robin (l.) and Chris Heath, Beaulieu 194

- Chris Heath

- UK Patent 645,897, 3 Mar. 1948

Acknowledgements

Text by John Miller Crawford, based on the following sources provided by David Carpenter, Bill Henderson, Edward Jones and Stuart Guy:

- Editorial obituary: Joe Mansour, Aeromodeller, January 1973

- Coles, R. History Of Beaulieu Airfield, Robert Coles 1982

- Lines, R. & Hellstrom, L. FROG Model Aircraft 1932-1976, New Cavendish Books, 1989

- John May, 'Trixie, Jumbo and Co', Aeroplane Monthly, May 1978 p. 261

- Hampshire - the county magazine, December 1990

- Personal correspondence of Bert Judge to Edward Jones

- Personal correspondence of A W Thatcher (Wilmot Mansour staff, 1961- ) to Stuart Guy (Head of Engineering, GEL Engineering Ltd)

Illustrations:

- David Carpenter, John Miller Crawford, Chris Heath, Alex Hutchison, Mike Ingram, Edward Jones, Howard Metcalfe, Aumann Auctions

Pre-Jetex Pioneers

First of the Flaming Flyers

First of the Flaming Flyers

Mr F W Thomas launches his rocket propelled model aeroplane at the Crystal Palace, London, in 1907.

A newspaper report of the time described him as "a tall man with a bushy walrus moustache, resplendent in top hat, frock coat and pin-stripe trousers".

Mr Thomas' model was described as "a weird contraption [...] not unlike an eccentric box kite".

As Dr Roger Simmonds, the source of this little-known footnote (or headnote?) to Jetex history, notes, "However, the model has some notable modern features, with plenty of wing area and adequate down thrust to cure excessive looping. Alas, the flight pattern is also all too familiar." As the newspaper report records:

Thomas launched the model into the air. With an impressive roar from its twin rockets it sped swiftly through the air, climbing steadily as it flew, but then disaster struck. It suddenly began to show ominous signs of instability, and a moment later it had dived into the ground so violently that it became an utter write-off.

Dr Simmonds adds: "The need for expert and careful trimming is obvious. Readers might like to know that the premier award winner at this particular model aircraft meet was A V Roe, flying an elastic-powered canard biplane."

HISTORY

Here we cover the story of attempts, both successful and unsuccessful, to power models using micro rocket propulsion. This story begins near the start of the last century and still continues into this third millenium.

Here we cover the story of attempts, both successful and unsuccessful, to power models using micro rocket propulsion. This story begins near the start of the last century and still continues into this third millenium.

Although the golden years of Jetex form a large part of our story, we also recount other efforts, both earlier and later, to achieve, and take advantage of, micro rocket propulsion. In particular, we tell how the introduction of Rapier motors has revitalised the flying of model aircraft designed for this form of motive power.

- Pre-Jetex Pioneers pays tribute to those who led the way with their valiant attempts to make use of existing forms of rocket power to propel model aircraft aloft.

- The Path to Jetex tells how the Wilmot brothers joined forces with Joe Mansour to form a creative partnership unique in the annals of model manufacturing.

- The Jetex Heyday records the full flowering of micro rocket propelled modelling – and not just the modelling of aircraft. We show how the imagination of designers, both professional and amateur, led them to explore the potential of Jetex power for all types of vehicles. In the field of model aircraft, though, this was the era in which designers and flyers, in an atmosphere of friendly but determined competitiveness, produced outstanding results in design and flight. We record and illustrate their achievements.

- From Heyday to Hard Times tells how the heyday continued for a time under other manufacturers. Gradually, however, troubling trends emerged – interest in micro rocket modelling was declining and the Jetex brand fell into the hands of less committed owners. The commercial production of Jetex motors and models came to an end.

- The Micro Rocket Revival looks at the current scene, where a number of new initiatives have produced a revival of enthusiasm for the unique appeal of this activity.

- Our subjects in this history are not just the engineering and design achievements, but also the people whose inventiveness, energy and resolve to pioneer new paths in model and motor design made possible those achievements. You will find the stories of the most notable among them in our Hall of Fame.

No. those associated with Jetex.org are simply Jetex enthusiasts. Roger Simmonds has some Jetex memorabilia for sale – books and tee-shirts, but not motors. Jetex.org has no formal relation to the pioneering individuals who invented and manufactured the Jetex product line. You can find out more concerning the creators of the Jetex.org website on our About page. Our primary goal is to bring the small yet geographically diverse rocket plane community together by providing an information service.

No. The last Jetex products came off the assembly line in 1972, so it has been quite a while since they went out of production. You can find out much more about the exact details in our History section.

In short, there were two companies involved in the manufacturing of Jetex products. Wilmot, Mansour and Co. Ltd. brought the concept to the market in 1948 and continued through the mid 1950s. Sebel took it from there until production ceased. Powermax made ‘Jet-X’ motors and pellets until around 2009 and their pellets should be used with caution in old motors. Beware of ‘Jetex fuel formulae’ sold on eBay and elsewhere.

It is better to use old stocks of genuine Jetex motors and fuel, and Roger Simmonds has links to supplies of fuse and, occasionally, other Jetex accessories.

There is an excellent motor, fully equivalent to Jetex, that is made in Poland, the TSP range of motors. These motors are single-use – a small cardboard tube with a ceramic nozzle. You use the motor once and then discard it. Please ask about current availability.

Jet-X, made by Powermax, was a similar concept (a reloadable metal motor) but came about much later. Production began in the mid 1990s and ended around 2009. Results have been variable in terms of certain vintages of fuel and overall weight of their 1997 Z series motors remains a concern.

We have an extensive listing in our Links section. Products and suppliers change from time to time. We keep our listings up to date and we recommend that you check that page often for new updated information.

It’s impossible to give a specific price on something like this. If you have one of the smaller, more common, ones that you flew with back in the 1950s or 60s (which would make it used … possibly very used) it probably isn't worth more than a few dollars or pounds. It is worth much more if it has never been fired and in its original package complete with various accessories. Some vintage Jetex motor outfits, especially the large sized ones, are quite collectable. Our Motors section shows most of the better known examples.

Collectors will collect anything! Large collections of motors in boxes etc are the aim of some modellers, others buy motors so they can be used for their original purpose. Enthusiasts will pay a lot of money for certain rare Jetex motors and it’s not unusual to find hundreds of pounds, dollars or Euros changing hands on eBay and at swapmeets.

This is certainly possible! There are enthusiasts using vintage motors to power their model planes or hydroplanes who have a good supply of vintage motors, fuel, and spare parts who will be happy to help you achieve your ambition. Motors for use, battered but usable, can be found on eBay, and Roger Simmonds can put you in touch with modellers with spares.

No! The earlier aluminum motors (mostly the Wilmot Mansour products) used a relatively cool burning guanidine nitrate fuel. Later steel motors (made by Sebel) used a hotter burning formula with slightly more thrust. Other ‘Jetex’ pellets contain ammonium nitrate. Sometimes aluminium-bodied motors are sold with Sebel pellets or V-Max pellets. This is most dangerous! There are many sad stories of folks who have melted their aluminum motors when using ammonium nitrate pellets. The steel motors, while being able to handle the ammonium nitrate fuel, weigh more. You won't damage them with the older guanidine nitrate pellets but, since that fuel creates a less aggressive thrust, you will have a less potent, though still satisfying, performance. There is still a fairly large number of the newer Jet-X motors with matching fuel pellets out there but these never worked as well as the earlier Jetex.

This is possible with enough resources. The motor itself is a relatively conventional and basic machine shop project (although most amateur-made examples we have seen are seriously overweight and their makers have a limited understanding of the safety features inherent in the classic Jetex designs). Making the fuel is the complex part as certain key ingredients are virtually unobtainable. It would take the efforts of an experienced contract laboratory – as opposed to that an individual chemist with lots of enthusiasm – to make it happen. Legislative concerns (licensing of premises, purchase of potent chemicals, quality control and distribution of products) would also need to be addressed.

No! Despite their similar physical appearance, there are many important differences. Regular model rocket motors (Estes, Quest, Aerotech, etc.) burn very quickly. The duration is usually less than a second and they are designed to be powerful enough to vertically lift a model rocket straight off of a launch pad. They would simply rip a conventional lightweight model airplane to sheds. For safety reasons, ignition occurs with an electronic controller at a suitable distance from the motor laden model. These well designed products are safe to use when the manufacturer's instructions are followed. But they are not suitable – and very dangerous – for use in a hand launched model aeroplane.

Also not recommended and potentially dangerous. The model would be very underpowered and likely to just sit on the launch pad and belch smoke. If the model did happen to make it into the air (on an extremely light rocket model, perhaps) it would still likely be underpowered and possess erratic flight characteristics. A Rapier is also not equipped with a delay charge at the end of the motor burn. This delay charge on a standard rocket motor is what pops the nose cone off so that a parachute can deploy. Without it, the Rapier powered rocket model will simply auger into the ground. With a low thrust and long duration Rapier motor in a conventional model rocket, the model is likely to spend more time on the ground than in the air. This makes it more of a fire hazard than anything else.

One of the simplest ways to get into the air is to adapt a classic balsa wood hand launched glider. Many of the vintage model shown in our Plans section are basically just that. If you have never done something like this before, this is a great place to start. More advanced modellers have successfully built scale copies of full sized jet aircraft and these are most impressive to see fly. Construction of these planes typically consist of a balsa frame with tissue covering, as you would find on a rubber powered prop plane.

Yes, and there seem to be more showing up every day. Many are classic Jetex designs that are scaled down slightly to accommodate a specific Rapier motor. There is also a number of simple all balsa profile models suitable for a beginner in this field. Please contact us for latest availability and prices. Other manufacturers and retail sources are listed in our Links section.

Yes! If there are fellow enthusiasts in your area or country, Roger Simmonds can put you in touch with them.